In 1 Samuel 1, we meet a man called Elkanah, husband of two wives. The first is Peninnah, who has multiple sons and daughters but appears not to enjoy particular affection from her spouse, and the second is Hannah. Hannah is loved by Elkanah, who is effusive and exaggerated in his declarations of affection for her, but ‘the Lord had closed her womb’.

Peninnah, not content with her superior fecundity, perhaps envious of Hannah’s place in her husband’s heart, takes great pleasure in rubbing Hannah’s face in her barrenness. Year after year, we are told, Elkanah travels with his family to the temple at Shiloh to offer sacrifices, and year after year at the sacrificial meal Peninnah provokes Hannah to tears. Think of a particularly vindictive Christmas dinner argument, the sense of a ruined occasion and a crystallisation of the family dynamic.

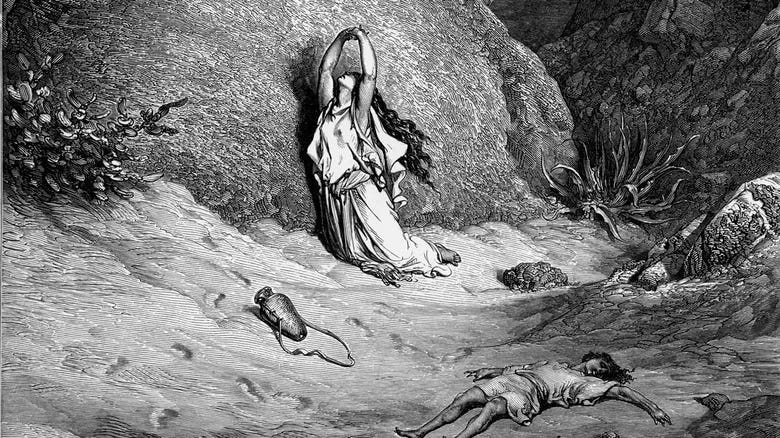

Humiliated and bullied in front of her family, Hannah goes off by herself to a quiet place to pour out her soul to God and beg him to give her a child. God answers in the form of Eli, a curmudgeonly old priest, half-blind, who berates her for what he assumes is drunkenness before realising his mistake and pronouncing a blessing upon her out of embarrassment.

This scene is a comical and clever retelling of another story of barrenness, of rival co-wives and divine messengers.

In Genesis 16 and Genesis 21 we are treated to the stories of Sarah and Hagar, wives of Abraham, opposites in every sense. Their nationalities, outlooks, status, piety, and treatment by God show them to be very different people. Sarah is the wife of Abraham, pretty enough to get him into trouble in strange towns, important enough to be given a new name by the God of the universe, privileged to be the mother to the child of divine promise, buried with care in a field bought specially for the purpose by her husband. Hagar is an Egyptian slave, acquired by Abraham or his entourage on their travels, passed from Sarah to Abraham to serve as a surrogate mother to their child, abused while pregnant by her mistress before running away to the desert, commanded by God to return and suffer again, only to be cast out permanently by Abraham at God’s behest, ending her days in the desert once again.

In 1 Samuel 1, we see Hannah dressed in the clothes of each of these women, as the biblical authors encourage us to see more of her character and the significance of her actions.

Like Sarah, Hannah finds herself childless and unhappy despite her husband’s affection for her, while her less favoured co-wife revels in fertility and scorns her barrenness. Only in these two cases– Sarah/Hagar and Hannah/Peninnah– does the Hebrew Bible tell a story of one wife being persecuted by the other over barrenness. Hagar suffers mightily in Genesis 16, undergoing affliction that the narrator describes using the same terminology as is used for Israel’s slavery in Egypt. Abraham and Sarah’s mistreatment of the Egyptian Hagar, and Hagar’s flight into the desert, is a brilliant setup for the story that unfolds in the book of Exodus, and the parallels between those two stories emphasise the injustice and misery of Hagar’s situation. Once she escapes from Sarah’s cruel hand, she is met by God in the wilderness, who mystifyingly commands her to return and suffer (the same affliction word is used) under Sarah’s control. God demands great obedience from Hagar, and Hagar comes through.

The writers of 1 Samuel portray Hannah in both of these roles; the mocked and childless wife provoked by a fertile rival, and the miserable would-be mother driven away to isolation to pray to God for help. By aligning Hannah with each of these two women, the writers invite us to make a choice: Who is Hannah really like?

Because neither picture quite matches up. Yes, Hannah is like Sarah in that she is childless and therefore slighted by her rival, but Sarah was given free rein by Abraham to discipline and punish Hagar, whereas Hannah’s own husband Elkanah simply tries to prove to her that her misery isn’t rational (a timeless caricature of husbands?). Like Hagar, Hannah goes off to a quiet place where she speaks with a divine figure, but Hagar is forced to this place by oppression and slavery, and she goes first pregnant then with her son. Hannah, by contrast, simply walks off because she wants to, and it is not as a pregnant woman or a mother that she stands before the Lord, but as a barren woman.

The writers help us work through this complex question by giving us extra information to tie Hannah to one of the two possible figures, Hagar and Sarah. First, Hannah calls herself a ‘maidservant’, an ‘amah, three times in a single verse. The repetition, once you notice it, is quite strange: “Lord of hosts, if you will look upon the affliction of your maidservant and remember me and not forget your maidservant, and will give to your maidservant a son…”

The repetition is dense, and it is not accidental: In Genesis 21, when Sarah tries to convince Abraham to exile Hagar from their family, the same word ‘amah is used of Hagar four times in three verses:

“Cast out this slave woman with her son, for the son of this slave woman shall not be heir with my son Isaac.” And the thing was very displeasing to Abraham on account of his son. But God said to Abraham, “Be not displeased because of the boy and because of your slave woman. Whatever Sarah says to you, do as she tells you, for through Isaac shall your offspring be named. And I will make a nation of the son of the slave woman also, because he is your offspring.”

On top of this, we also get the phrase “look upon the affliction of…”, which carries its own allusive possibilities. In the first story of conflict between Sarah and Hagar, we are told that Sarah takes advantage of Abraham’s lax leadership to ‘afflict’ (a.nah) Hagar. This affliction is what God commands Hagar to return to, when he meets her in the wilderness a few verses later: “Return to your mistress and be afflicted by her (again the word is a.nah, but most English translations don’t make the reuse of the word clear, presumably because it’s hard to convey the idea of submitting oneself to affliction in a single word). The word is used a third time in the story, when God pronounces a prophecy of blessing over Hagar and Ishmael, and says that he has “listened to your affliction”, using the word o.ni, which is simply the same word a.nah in the form of a noun instead of a verb.

In short, the writers of 1 Samuel 1 have Hannah speaking to God in words that come from the life and trials of Hagar, not of Sarah. The use of these words and phrases helps us as readers to reject the possibility of Hannah being Sarah-like and instead to embrace her Hagar-ness.

What does it mean for Hannah to be like Hagar?

First, it makes the reader pause. This complex, layered, question-provoking portrait of Hannah, placed as it is as the opening of the book of 1 Samuel, ought to make us proceed very carefully. If this is how much we have to think about how to evaluate Hannah, how much more will we have to be careful with Samuel, or Saul, or David?

Second, it suggests the possibility that things in Israel have fallen far from the ideal. Hagar is a slave woman, used by Sarah and Abraham to try to fulfil a divine promise by their own means, who disappears from the story in Genesis 21 along with her son Ishmael and never returns. If Hannah were compared to Sarah, we could see her son Samuel as a child of promise, a continuation of the covenant, a link in the unbroken chain stretching back to the beginnings of Israel. But she is not like Sarah, she is like Hagar. Hannah is paired with the road not taken, the second-choice spouse. What if the story of Israel has become so degraded and misguided that we should no longer think of it as God’s people, but as an offshoot? What if this is a second-best story?

Third, the son of Hagar is Ishmael. Not the promised child, not the beloved son, not the only son of the great patriarch Abraham, as Genesis 22:2 calls Isaac. Samuel, the son of Hannah, is not paired with a child of hope but with a product of faithlessness, oppression and coerced conception, ‘born of the husband’s will’ we might say. This is one of the earliest clues in the book of 1 Samuel about the character and destiny of Israel’s great king-making prophet.