Football TV Commentary & the Creation of History

And Martin Tyler said, "Agüero", and behold, Agüero.

This post is a one-off, I hope you enjoy it so much you can’t help subscribing. Next week, Peter Thiel!

I.

Here is a simple pie chart.

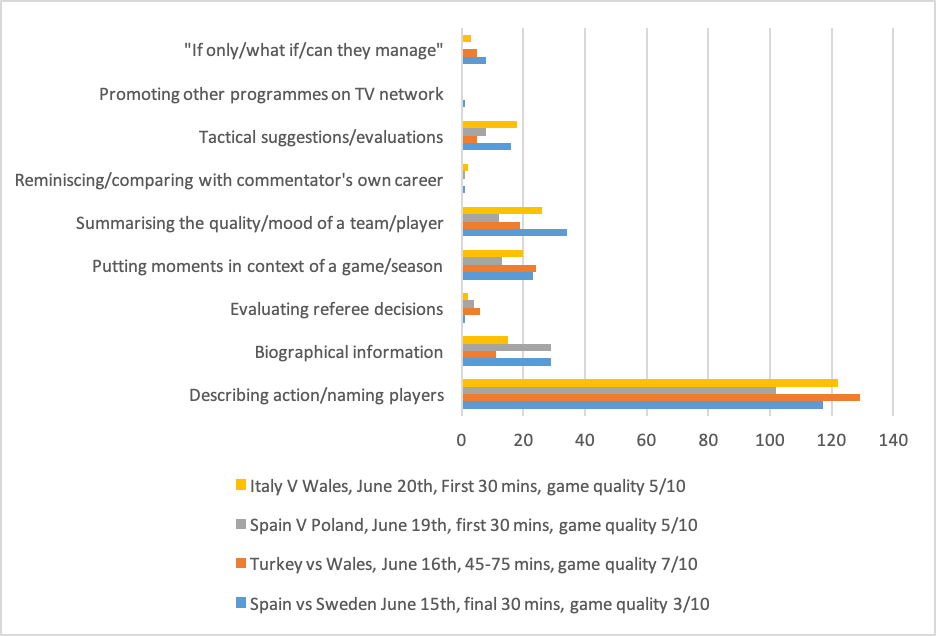

The chart represents some data I compiled from four 30-minute periods of football games in the Euro 2020 group stages and Last-16. In essence, I sat with the Notes app open on my phone, and every time one of the commentators spoke I noted which category their comments fell into. Here’s a different chart, broken down by each game, to help explain some more.

Not all four games had the same commentary teams, and as shown the games were of varying ‘qualities’ (my own entirely subjective evaluation, based on how bored I was at the end of the 30-minute period). Some commentary teams were, on the whole, more talkative than others, as shown by this third helpful chart (N.B. this is not the number of minutes taken up with speech, but the number of times a commentator spoke).

As we might have expected, the commentators in the most boring game (Spain v Sweden, what a drag that was) talked a lot to fill the time and make up for lack of on-pitch entertainment. The games that were boring (SPA-SWE) or featured teams whose players are less familiar to a British audience (POL-SPA) went much heavier on providing biographical information about players, coaches, stadia and fans. In the first case this was probably to provide some interesting diversion, in the second it served to allow the audience to engage emotionally by providing points of contact and orientation (you don’t care about a Polish central midfielder whose name consists entirely of the last eight letters of the alphabet, but you’ll care a little if you know his mother played competitive ice-hockey in the former USSR. Won’t you?)

Clearly the most significant category is the one we probably expect from football TV commentators: describing the game. This takes up around 60% of the commentator’s time, and is divided between simply naming the player currently in possession of the ball (“Morata, Torres.”), narrating a passage of play (“Pickford plays it out to Stones, under a bit of pressure there but he’s dealt with it comfortably.”) and the slightly-more-abstract mini-summarising of rapid events (“The Czechs were pressing there quite dangerously but now it’s them who are under pressure as Croatia look to break, and here comes Modrić”). It is this category of description that fascinates me, and which I think points to the true magic– and tragedy– of the football TV commentator.

II.

What is the point of someone describing to you the events that are unfolding before your eyes?

A certain school of thought would respond that whoever controls the narrative controls everything, since power dynamics are shaped by the stories in which they play out (pun intended, we are still talking about football). Thus the person whose narration of events dominates also dominates everything else. This has a certain unavoidable logic to it, and not only in the postmodern scrum; Genesis 1 depicts a God whose power of speech spills over from the descriptive into the creative– God’s narration actually makes things happen. Solzhenitsyn (I’m not going to check how to spell his name in the hope I’ve got it correct first time) famously characterised one of the great evils of life in the Soviet Union as the pressure to speak constantly in lies one knew to be lies, to perpetuate impossible falsehoods that everyone in the conversation knew to be false but continued to sustain. So, clearly, to be a legitimate narrator is to wield some sort of power over the world.

A more benign (and hopefully more familiar) version of this idea is that of the guide or teacher. Children’s books teach by narration, be it biology or mathematics or geometry or music. David Attenborough and his TV programmes have successfully instilled in an entire generation of British viewers the instinct that it is correct and natural to assume that wild animals (lions, eels [yes I know an eel is technically not an animal], komodo dragons [likewise] and capybara alike) somehow feel exactly the same emotions of pride, unease and elation as would humans in the same situation. His narration, the tone of his voice and choice of his words, shape almost completely the world that appears in image-form. The upside of this is that it allows the show’s writers to soothe the conscience of viewers when the animals that have just been so powerfully dignified with human emotions then begin to rape, dismember and obliterate one another– these things can be narrated away as simple obedience to the harsh laws of nature, probably somehow ultimately the fault of human environmental negligence etc. (Yes I believe humans have negatively impacted the environment, my point is simply that it is patronising to tell viewers that maybe if they cycled to work then cheetahs wouldn’t flay the skin off living wildebeest because they’d all be living happy lives elsewhere as vegetarians [this is hyperbole, I have no evidence Planet Earth makes this claim]). I have strayed from my point, which is this: narration is a very helpful tool we can use to induct others into the world of things that are very complicated to explain but not very complicated to inhabit or experience. I can describe the change of the seasons and their impact on the vegetables in my garden without remembering a single piece of high-school geography/biology, and my description will suffice as long as no radical change occurs in the progress of the seasons (see climate change non-denier status above).

And in football? Why do I need someone to describe the very events I can see with my own eyes?

One option is that the commentary is for the uninitiated, providing a gentle introduction to complicated rules, unfamiliar tactical choices, and generally functioning with a constant “For those unfamiliar with football” disclaimer before every sentence. Similarly the naming of players whenever they play a part provides information that seasoned fans would already have (people who never succeeded in mastering french vocabulary, maths formulae or all the different road-signs will joyfully list six or seven core members of every Premier League team for the last five years), but which newbies and casual viewers need provided moment-to-moment. If this is the case, it is a little depressing, since it assumes A) most football viewers are very stupid and impatient (how many times do you need to see a player fouled before you work out the dos-and-don’ts?) or B) those new to football-watching are in a context where asking any questions about the mechanics of the game is utterly impossible. Certainly it would get annoying to be asked to explain every single piece of action over a 90-minute game, but if someone is interested in following a game surely they will also be paying enough attention not to need reminded what a free-kick is every time it appears (33 times on average per game, google says).

The other option (the one you probably assumed from the start) is that football TV commentary exists for those who already know exactly what’s happening. The implications of this reveal something about the state of the world.

III.

Implication the first: Even when we are experienced, mature participants in group activity, the simple affirmation of our perspective is comforting to such a degree we can’t let go. I don’t need anyone to tell me that a goal has been scored– in fact, if I was watching football and anyone in the room felt the need to turn to me and inform me a goal had been scored, I would probably make some sarcastic comment about how I hadn’t noticed, since I was only looking at the TV screen and hence had no way of knowing what was happening in the game… But when the commentator narrates a goal being scored, it serves as the focal point for all sorts of emotions among the viewers. The authoritative (canonical?) interpretation provided by the commentator creates a piece of common material that can be shared by all sorts of people, far more easily than the simple viewing of the game can do on its own. Even though I have watched perhaps a hundred hours of football (perhaps more? It’s hard to say), the reassurance of the commentator’s voice affirming the thoughts I am thinking in regard to the game is profound. This is connected to:

Implication the second: Our culture is so over-saturated with commentary, oversight, regulation and critique that events do not feel momentous without someone telling us how momentous they feel. In other words, the ability to perceive the value of a moment has been scrubbed out of us. I can tell when a goal has been scored, even if I am only watching with half my attention, even if the commentary is in another language, even if there was no commentary at all, yet an un-commentated goal feels strangely flat and illegitimate. Did they really do it? Was it an offside? The lockdown restrictions kept fans out of football grounds for a year or so, and despite the rash of banners and adverts declaring football to be ‘nothing without the fans’, and despite the commentators’ own expressions of how much worse football is without crowds, still the games went ahead and millions of people watched online. In contrast, have you ever watched a game of football without commentary– except in-person? The narration provided by commentators imposes a shape on the game, and most importantly it takes the responsibility of evaluating and discerning away from the viewer. Our feelings may be shaped by what is happening on the pitch, if we are especially attentive, but 9 times out of 10 it is the commentator’s voice that leads us. Goals seem to come out of nowhere, fouls are judged to be slight, all because of a few words from the authoritative narrators. The perfect example of this is the legendary commentary by Martin Tyler of Sergio Agüero’s era-defining goal. Tyler’s voice tells the entire story of the emotion of the moment, the nerves and sense of “is this really about to happen?” are conveyed by his tone and pitch, and the iconic “Agüero” itself has to be heard and cannot be described. It contains a full life of experience, and will perhaps never be surpassed as a piece of joyful, awestruck (in the non-hyperbolic sense) narration-reaction. What follows that joyous moment is a perfect example of:

Implication the third: The self-conscious nature of football TV commentary destroys the very thing it is dedicated to complement and serve. In the moment of Agüero’s goal, the entire stadium and thousands of homes around the country were swept up in a wave of emotion. Pure in-the-moment stuff, feeling the shock and joy of the phenomenal goal, the emotions that constitute experiencing greatness. In Tyler’s commentary, this almost immediately is destroyed as the commentator tries to narrate these inner feelings and can only do so by committing the show-and-tell error. If something is great, don’t tell me that it’s great, just tell it to me and I will experience its greatness. Tyler pivots from partaking in the greatness of the moment to start telling the viewers that what they are watching is a great moment, trying to heighten the meaningfulness of the moment and destroying it in the process. It’s similar to the introspective problem of happiness: If you are happy, you are not thinking about how you feel, you are thinking about other things and these produce happiness. If, while you’re happy, someone asks you how you feel, you stop thinking about what you were thinking about, you start thinking about your emotional state, and all of a sudden the happiness evaporates as your attention shifts to something else. In his commentary, Tyler (and every other commentator of even remotely great moments in football history that I have experienced) does exactly this. He stops narrating the action and instead turns his focus to the inner emotional state of his viewers, and so splits their focus: the eyes see the moment of greatness and its aftermath, the ears are turning the attention inward, and consequently the viewer is stuck in a fake, duplicitous state of trying to simultaneously enjoy the moment and watch themselves enjoying it at the same time. It would be easier to look at the underside of your feet while standing on the ground.

IV.

None of this is the fault of the commentator. We all do these things, in a hundred areas of life, every day. But the football TV commentator provides a snapshot of all of us, in our particular hopeless lost culture: imposing shape and order on games that are only meaningful because we fill them with meaning, striving to build a dramatic and significant history in-the-moment every moment as if laying the track for a train whilst tied to its wheels, and not realising that by turning his attention to the greatness of what is in front of him he destroys both that greatness and his ability to perceive it.

They think it’s all over– maybe they’re right.